Uncle Ed, my father, unknown buddy (c. 1942)

“When Lowell and I quit Junior College we went to Lodi and lived with your parents until the war. We enlisted shortly after. Your parents made several moves before they lived on 21 West Third Street in Stockton. While on Third Street your dad and I got jobs driving dump trucks at the Stockton Airport.” Ed Willems[i]

It must have been in the summer or fall before Pearl Harbor that my family moved to Stockton, to Third Street, south of downtown. My father’s youngest brother, Ed, said that he and my dad got jobs driving dump trucks at Stockton Airport. The airport was on the south side of town. Looking at the map of Stockton, I can see that our house on Third Street was just a short drive from the airport, a convenient location for Dad and Ed. I remember the house on Third Street. It was old, poorly constructed and tiny. It sat on a huge lot with some big trees along the property edge. Behind it was a small barn. This must have been where Ed and Lowell slept before they joined the Navy—barns seem to have been a regular bedroom adjunct for my family back then.

We did not stay on Third Street for long. In the fall of 1942, my family moved again, this time to an almost-new house on Coronado Avenue, which was on Stockton’s northern edge. We stayed in that house seven years. I was four when we moved in, eleven when we moved away. This house is where memory becomes clear and distinct.

Dad said he paid $4,000 for the house on Coronado, a real step-up from the $1,100 he paid for the house on Third Street. It was a pre-war house, probably completed just before Pearl Harbor when home construction basically came to a halt, the nations’ labor and capital diverted to war production. Like most homes of its age in California, the exterior was stucco. The house had two bedrooms, one bath, a living room with a bay window, and an eat-in kitchen with an adjacent utility room that opened into an attached garage. It wasn’t a large house, probably about 800 square feet, average footage for houses in that time. Though small, it was well-built. It had hardwood floors, plaster walls and real ceramic tile in the kitchen and bathroom, cheerful pale yellow tile with shiny black trim. Mom and Dad had never had a new house before, and I’m sure they were excited about it. They ordered custom-made venetian blinds for all the windows as soon as we moved in, and Mom made pinch-pleated, lined drapes with swag toppers for the bay window in the living room.

The only lawn was a patch of clover right in front of the house, which became a buzzing carpet of bees in summer, a bee-sting gauntlet for bare feet. As soon as weather allowed, Dad brought in a tractor and plowed, leveled and seeded the rest of the big yard with regular grass, blue grass, he said. He also planted young walnut trees spaced so they would eventually shade all of the yard except the vegetable garden across the back of the lot.

There were just the four of us in the new house: Mom, Dad, my little sister Nita and me. My uncles and their buddies were gone, away at the War. They were present now only as photos in the album on our coffee table and infrequent letters. I knew that Uncle Ed was still in Florida, and that Uncle Frank had been drafted into the Army and sent to Hawaii for basic training. When he got there, Uncle Frank sent me a paper lei and hula skirt, a real grass one—not one of the cheap, bright colored imitations I scorned. Mom took a snapshot of me wearing the skirt and lei and sent it to Uncle Frank. Under the lei and grass skirt I was wearing a silk bra and matching panty that Mom made out of an old silk dressing gown given to her by one of the neighbors on Third Street. It was too worn under the arms to wear, but still had good fabric in the long, full skirt. The colors—Chinese red with small blue, yellow and white flowers—were still bright, not the least bit faded.

Me, in the grass skirt and paper leis Uncle Frank sent when he was stationed at Pearl Harbor.

Although my uncles and their buddies were gone, my world was not emptied of men. Dad was never called up, and only one of the fathers in our neighborhood, the man across the street, was in the service. In fact, Stockton seemed full of men. Stockton Field was a pilot-training school, and Stockton was a deep water port with access to San Francisco Bay. Sailors were a familiar sight in town. It had nine shipyards, and the Navy had a pier at the port. To top it off, the Western Pacific Railroad ran right behind our back yard. Trains packed with young men rattled by every day. I would wave to them, and they would wave back at me. In the summer when the windows of the cars were open, I could hear them whistle and shout at my Aunt Sylvia, Mom’s teen-aged sister, who loved to lay out in her swimsuit on the lawn in our back yard where all the guys in the train could see her. This was the war for me, these handsome young men and pretty girls flirting with them—energy, sexual energy, optimism and people going places, doing things.

Mom

On December 7, 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, my mother was twenty years old. When Japan surrendered in August 1945, she was twenty-four. That war, in a very real sense, belonged to her generation. It was her age cohort that provided the young men who fought in it, and the young women who took their place in the work force on the home front. The war brought together masses of young adults, gave them a mutual high purpose. There was danger, there was fear, but there was also a strong sense of high adventure. They were part of something huge and terribly important, something that focused energy and gave it a concrete goal. It was an exciting, electric time to be young. My mother was not a Rosie the River. The center of her life was her home and family, but she, too, experienced the calling forth of energy and high purpose.

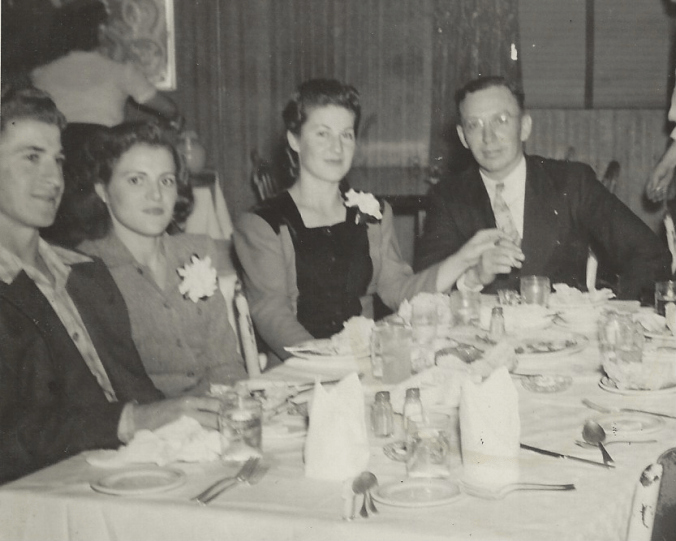

Mom came into her own during those war years. She was competent and confident, the calm center of our home, a responsible, dependable presence. And she was beautiful. She had an oval face, lovely blue-green eyes, glassy dark brown hair and a perfect figure: 36-26-36, she told me. She was beautiful, and she enjoyed her beauty. Even as a small girl I could see the admiration in the eyes of my father and his friends when they looked at her. I shared their admiration, proud that she was my mother. We were not a picture-taking family, but I do have one picture of her taken during the war, one made by a photographer at a night club. Mom is in the center, holding my father’s hand.

My mother’s youngest brother, Reuben Young; his wife, Delores; my mother, Agnes; my father Jack Willems (c, 1944)

[i] Ed Willems, e-mail: 2-18-2008

[ii] militarymuseum.org/StocktonField

You have captured the spirit of the war so well, Loretta! I was about your age at that time and have some memories of the war, but not as many and not as sharp as yours.

LikeLike

Thanks, Loretta. It’s nice to know that someone else who was a child during WWII experienced the war in much the same way I did.

LikeLike