“The only observations worth making are those that sink in upon you in childhood. We don’t know we’re observing, but we see everything. Our minds are relatively blank, our memories are not crammed full of all sorts of names, so that the impressions we gather in the first 12 years are enormous and vivid and meaningful—they come laden with meaning, in a way that experience does not later on.” John Updike

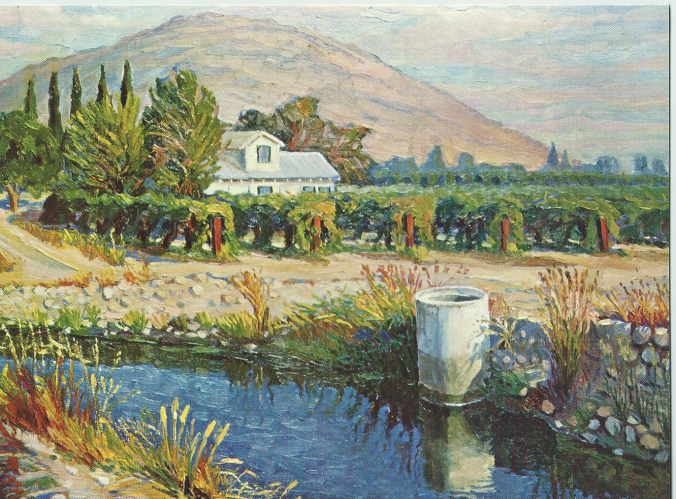

Paul Buxman: The Farm on Annadale Road*

Until the winter I turned three, New Year’s Day 1941, my parents and I lived in the area around the town of Dinuba, California where my father’s family lived. Those were some of the hardest years of the Depression, and Dad really scrambled to feed and house us, picking up whatever job he could find—driving tractor, pruning vines and fruit trees, working the raisin harvest, doing short order cooking, pumping gas at service stations, driving truck. Then in the late fall of 1939, just before I turned two years old, Dad made a deal on a small farm, 26 acres of grapes and alfalfa near a little community sixteen miles north of Dinuba called Navelencia.

This is rich farming country, a land of vineyards and orchards and orange groves, located in the southeastern part of California’s great Central Valley. This land lies at the feet of the Sierra Nevada range where those mountains reach their greatest height. The craggy peaks that surround 14,495-foot tall Mt. Whitney are just fifty miles east of Navelencia. Twenty-five miles due east is Grant Grove in Kings Canyon National Park, a spectacular stand of giant sequoias. Those trees stand at an elevation of 6500 feet, more than a mile above sea level, more than a mile, too above the farm where we lived. Only twenty-five miles apart, but two very different worlds, the high land a place of big trees, green meadows and sparkling streams, the land below a hot dry alluvial plain that spreads out around scattered foothills in a sloping descent to the valley bottom. Navelencia, with an elevation of only 350 feet, sits on the plain about four miles southeast of one of the last of the big foothills, 2092 foot tall Jesse Morrow Mountain.

Our farm was completely dependent on those mountains. Our rich soil had its origin in their steep slopes. Our water was the gift of the high peaks that catch Pacific Ocean moisture, store it as deep winter snow that slowly melts into the root-mass of the big trees. The roots hold the moisture like a great sponge that is able to seep water all summer long into rivulets and streams that feed the Kings River that tumbles out of the mountains, down the foothills into Pine Flat Reservoir ten miles north of Navelencia. Without that water and the irrigation canal that brought it to us, there would have been no farm, no grapes, no alfalfa, no trees—for this is a land of little rain. The crops our land produced loved the abundant sun that comes with cloudless skies, but they could not survive on the 12 inches of precipitation that is the annual average for that region.

Memory begins at Navelencia[i], on the little farm where I lived between my second and third birthdays. Before that, all is dark. The names Pixley and Hollister and Sultana–other places where my parents found a bit of work in the years after I was born evoke no images at all. But when I think, “Navelencia,” I can suddenly ‘see’. I see the pale tan of the dirt driveway that led from our house out to the road; I see that same smooth tan on the strip of land between the road and the big irrigation canal that curved around the south side of our land. I see that water flowing deep in the canal.

I have no memory of the house we lived in, just a vague impression of a small, dark place that seems to be in a clump of trees on the middle of the property. I can’t see the house because I am standing on the packed dirt of the driveway with the house behind me. I am looking east. On each side are open fields. Up ahead, on my right, I see low weathered outbuildings and a tall wood fence that encloses a big pig-pen that sets in the corner between the drive and the road. There is a sow and her babies in the pen I know, but I don’t really see them. What I see is the long driveway, the canal and the road that parallels it.

I also have memories of a few events that took place on that farm. I remember getting hooked on the front bumper of a car and being dragged down the driveway as the car slowly backed towards the road. The car belonged to a salesman, I think. It didn’t go far before I was discovered. I wasn’t really hurt, not even scared by what happened. The adults, however, had been badly frightened, and they took me to a doctor who said I was fine and obligingly painted me red with mercurochrome so I could have something to show for my visit.

In another memory, I am standing on the bottom rail of the pigpen with my hands holding one of the higher rails. I want to show our pigs to a little neighbor boy who is standing on the drive. He is scared of the pigs and won’t get near the fence. I am disgusted; think he’s a sissy.

An even stronger memory takes place out on the road that runs alongside the big canal. I am running north as fast as I can towards a small country store that I know is up ahead of me. There is candy there, and I want to get some. I’m not sure how far I actually traveled before my very worried parents caught up with me. They kept asking me why I had run away, and I couldn’t get it across to them that I wasn’t running away. I just wanted to get some candy.

Knowing my father, I must have gotten a good scolding. I had been told over and over to stay away from the canal and not go out on the road. My parents were very anxious about me falling in. I really did understand that I should not get close enough to slip and fall in. I kept a careful distance—but I was not afraid of it.

I liked water, and my lack of fear worried my folks. One day while my dad was out irrigating the grapes he decided to instill what he thought would be a healthy scare. I was out in the field with him and kept ignoring his command to stay out of the feeder ditch, which was shallow enough in places for me to walk. Exasperated, he finally picked me up and threw me into some water that was over my head. I thought he was playing. “Oh, fun, daddy!” are the words my dad remembered until the end of his life.

Looking back I can understand the fear and worry I felt in the adults around me. A curious, fearless two year old who loves water, living on a place surrounded by water is a rather terrifying idea. That farm was a dangerous place for a small child intent upon exploring the world around her. There was the water, there was a direct-current electric fence that killed my dad’s favorite horse, and there were the pigs. I liked the pigs that grazed our alfalfa and drove my dad crazy by swimming the canal and getting into our neighbor’s grapes. I liked the sow and her little piglets. But big animals of any kind are dangerous to small children—particularly a mother pig. Sows are capable of killing even adults if they sense their babies are in danger.

But that is my adult assessment, not that of the two year old, and it is the feelings and perspective of the two year old that I remember and still feel. What I remember is the eager reaching out to the world, the curiosity, the desire to explore. But what I remember most is the place itself–the soil, the water, the cloudless sky.

_______

*Re the scene in the Paul Buxman painting: The mountain that fills most of the horizon is Jessie Morrow Mountain, the mountain almost directly north of my parents’ farm. When my dad took me to see the farm in 1994, I was astonished to see it. It was huge, yet I had absolutely no memory of it. Was it too big for me to see?

i] Navelencia is an unincorporated farming community, named for the two varieties of oranges that grow on the surrounding farms—Navels & Valencias.

What wonderful memories. Childhood really is a special time; we just don’t realize it at the time.

LikeLike

I’m glad you enjoyed the memories. Hope you continue to enjoy them, because I will be posting more. I does feel more than a bit self-indulgent, but I keep telling myself that it’s ok. Knowing other people find them interesting helps the self-doubt.

LikeLike

Hi Loretta! Sure enjoying reading what you have written so far. I share these same memories of the area that you write about and it brings a smile to my lips. Did you ever eat “dirt”. On those hot summer evenings, after sprinkling the ground, it would smell so good that I would taste it. I now understand that this probably was caused by a lack of some mineral in my body. I guess all children must be drawn to water because I remember going to swim in the ditch down the street. It was gross with broken bottles strewn all over the bottom and I think people also threw dead animals in there but still that attraction to that cool water on those hot summer days in the valley was like a magnet.

LikeLike

Hi Marilyn. Love your memories. The intense Valley heat was not part of my memories, but I’m sure it was, as it was for you, the reason water was such a magnet. –I don’t remember eating dirt, but probably did try it as some point.

For some reason your “ps” got sent to me, but not this comment. Found it just now.

LikeLike

P.S. Love that beautiful painting that Paul did. Just captures the area!

LikeLike

Yes, Isn’t it beautiful. I want this painting to be the cover of my next book.

LikeLike

Beautiful writing, Loretta. I am “seeing” with you. I’m astonished at the “feeling” of yourself you remember as such a small child and have communicated here. I don’t have that for those years of myself. The painting is wonderful too.

LikeLike

How nice to read your words, Dora. If my family had stayed on the farm in Navelencia I doubt that I would have remembered these early feelings. There was a feeling of loss in that move, a yearning for this little farm that stayed with me until I wrote this piece back in 2001. As far back as I can remember these memories would periodically surface, and I would hold them in my mind, look at them, in a sense send myself back to that place and time—thus carrying them forward as my mind developed.

LikeLike

Just a little older than you, Loretta, I lived at about the same time in Castroville, on the coast, and have some vivid memories of three or four events which my parents did not remember at all — interesting, the mind of a child!

LikeLike

If you have written these, or write them up at some point, I would love to read your memories, Loretta

LikeLike

I got caught up in this piece – the setting and the memories seemed so vivid to me. I really liked how you were able to express your memories through the senses and feelings of the child. I also like the part near the end where you mention the sense of eagerness, curiosity and exploration that you felt as a small child.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comments, Trueda. They are helpful.

LikeLike